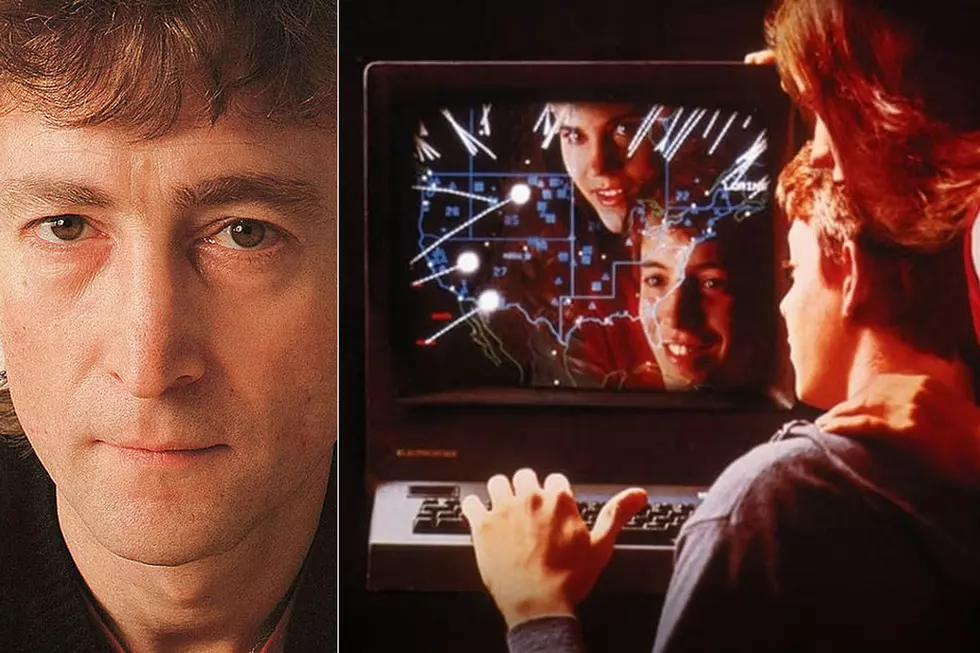

What if John Lennon Had Starred in ‘WarGames’?

Sometimes you get your point across despite the medium. The 1983 movie WarGames proved that in its development history.

Regarded by some on the business side as a quirky kids’ science-fiction romp about a wayward student named David (Matthew Broderick) who has one of those newfangled computer things at home, WarGames was actually a thought-provoking story about how we can wind up living life as an un-winnable game if we're not careful.

In the script, David uses a dial-up modem to contact other computers that can be accessed via the early internet. He initially uses his ability to improve school grades and steal prototype video games. He begins using brute-force attacks where the computer is left to try every option, no matter how long it takes. This results in a connection with a mystery machine that’s incredibly powerful. Turns out, it’s WOPR, the American military computer tasked with using all the intelligence it can amass to ensure a U.S. victory in a nuclear war.

WOPR’s creator is a key character in the story. He’s become a recluse, angered and saddened by the way of the world, along with the loss of his son Joshua and wife in a car crash. He’s the voice that steps in when the AI computer – which he also named Joshua – begins playing a game called Global Thermonuclear War, and the military staff believe the final battle has commenced. Along the way, WarGames popularized the Defense Condition numbering system, moving from all’s-well DEFCON 1 to all’s-going-to-hell DEFCON 5.

The creator was named Stephen Falken, after the real-life Professor Stephen Hawking. In the late ‘70s, future DreamWorks boss Walter Parkes had co-written a script with Lawrence Lasker, then titled The Genius, and wanted Hawking to play the Falken role. The producers balked, worrying that it would look too much like the 1964 dysto-satire Dr. Strangelove. The next choice was John Lennon.

“We always pictured John Lennon, because he was kind of a spiritual cousin to Stephen Hawking,” Parkes told Wired in 2008. Lasker confirmed that they “communicated with John Lennon, and he was interested in the role. I was writing the first scene where we meet Hawking – Falken – in the movie. He was an astrophysicist in our second draft. I was staring at the cover of the November ’80 issue of Esquire, with Lennon on the cover, and describing his face, when a friend of mine – a bit of a jerk – called and said, ‘You’re gonna have to find a new Falken.’”

Watch the ‘WarGames’ Trailer

Lennon’s subsequent murder became a seismic event. WarGames moved forward without him, taking in $80 million from a $12 million budget while garnering three Oscar nominations. Had he been able to appear as Falken in WarGames, it’s reasonable to assume its impact on release on June 3, 1983, would have been greater. British actor John Wood delivered an excellent performance in the Falken role, yet it’s very clear the spirit of Lennon lives within it.

Would he have wanted the role? It’s impossible to say for certain, but given the subject matter, it’s at least likely. The Beatles became known for pushing the boundaries of studio technology, so it follows that he’d be interested in the home-computer revolution.

“John would have been totally excited about the computer age, because that’s the kind of thing that John and I were dreaming of,” Yoko Ono told Rolling Stone in 2013. She has also said: “he would have been very interested in playing [on] the computer, because he always jumped on some new media and that is a very interesting new media.”

Former bandmate Paul McCartney is certain that Lennon would have embraced all forms of technical developments – even the controversial Autotune vocal effects processor. “I’d say that if John Lennon had had an opportunity, he would have been all over it,” McCartney told the Independent. “Not so much to fix your voice, but just to play with it.”

More critically important is whether Lennon would have appreciated the message of the movie – and the answer surely must be yes. Right up until the end of his life, he was taking opportunities to berate world powers for their use of aggression, even though he’d become less of an activist about it.

Lennon acquitted himself well in front of the camera when he appeared in the 1967 movie How I Won the War, playing Musketeer Gripweed in the dark comedy set in a war zone. He delivered a subtle, underplayed performance that drew approval from critics.

“I feel I want to be them all – painter, writer, actor, singer, player, musician,” he said during shooting. “This is for me, this film, because apart from wanting to do it because of what it stands for, I want to see what I’ll be like when I’ve done it.” Gripweed turned out to be Lennon’s only movie role, but it offers insight into how he might have approached Falken.

Watch the ‘Shall We Play a Game?’ Scene From ‘WarGames’

The opening scene in WarGames is almost imaginable as a scenario created by Lennon himself. A human-staffed nuclear bunker receives a launch command and its two officers go through the motions to check and confirm its validity. Seated a distance from each other, both must turn a key to release the missile at the same moment.

Seconds roll by, and the captain refuses to complete the procedure. His junior officer aims a gun at him, shouting: “Turn your key, sir!” The captain responds, “I want somebody on the goddamn phone before I kill 20 million people!” The launch command wasn’t real – and the question of how it could have been completed if the captain had been shot isn’t dealt with – but it’s enough for military command to decide computers should commence the destruction rather than people.

It's easy to imagine some lines being spoken by Lennon. For example, when Falken explains to David why he built Joshua, he argues that “the whole point was to find a way to practice nuclear war without destroying ourselves, to get the computers to learn from mistakes we couldn't afford to make. Except, I never could get Joshua to learn the most important lesson: Futility, that there’s a time when you should just give up.”

Challenged by David on his underlying attitude, he cites the example of playing tic-tac-toe as an adult: “There’s no way to win. The game itself is pointless! But back in the war room, they believe you can win a nuclear war. That there can be ‘acceptable losses.’”

Falken offers a fable to support his argument, playing a dinosaur film. “Once upon a time, there lived a magnificent race of animals that dominated the world through age after age. They ran, they swam, and they fought and they flew, until suddenly, quite recently, they disappeared,” he said. “Nature just gave up and started again. We weren’t even apes then. We were just these smart little rodents hiding in the rocks. And when we go, Nature will start over. With the bees, probably. Nature knows when to give up, David.”

Toward the end of WarGames, he argues with the war room commander who’s convinced the Global Thermonuclear War game is a display of what’s actually happening out there. Falken urges the commanders to tell the president to wait it out. “General, do you really believe that the enemy would attack without provocation, using so many missiles, bombers, and subs so that we would have no choice but to totally annihilate them?” Falken asks. “General, you are listening to a machine! Do the world a favor and don't act like one.”

In a modern world of AI, drone warfare and cultural disagreements, the argument remains valid.

Watch the Closing Scene From ‘WarGames’

The Falken character also shares Lennon’s famously dark humor. At one point while discussing the war games, he said he “loved it when you nuked Las Vegas. Suitably biblical ending to the place, don’t you think?” Asked how he plans to survive the looming destruction, Falken says he’s “planned ahead. We’re just three miles from a primary target. A millisecond of brilliant light and we’re vaporized. Much more fortunate than millions who wander sightless through the smoldering aftermath. We’ll be spared the horror of survival.”

In the final scene, as Joshua runs a brute-force attack to guess the launch code that humans won’t give him, Falken encourages David to pursue his aim of making the computer play itself at tic-tac-toe. The military bosses see that David has gained access to Joshua and shout at him to order a shutdown or to place an “X” in the grid center to try to win the game, but David succeeds in forcing Joshua to learn what it had to learn.

Joshua has secured the complete launch code, but gives up on tic-tac-toe and applies the same process to every missile strike pattern it can come up with. With each pass, the conclusion is “Winner: none.” The lights go down, then Joshua speaks into the darkness: “Strange game. The only winning move is not to play.” It could be a John Lennon lyric.

The Oscar nominations for WarGames were in cinematography, sound and script. If he’d been part of the production, Lennon would almost certainly have influenced the film. Could playing Falken have made it into an Oscar winner? Could Lennon have won an Academy Award himself? It seems not entirely impossible.

In the script, an intelligent young person who can’t fit himself into the rules of society is regarded as a problem. The world around him has gotten itself into a mess where it won’t trust a kid who refuses to accept the rules, and they can’t trust a computer incapable of adapting those rules according to context. Isn’t that at least a rough summary of Lennon’s own interaction with the world – but with music instead of microchips?

A notable part of Falken’s character is that he totally believes in David, encouraging him to follow his gut instinct and apply his intelligence, even while the world is set to end if he gets it wrong. It’s not difficult to imagine Lennon behaving that way, passing on the torch, prepared to step into the shadows.

“I hope we’re a nice old couple living off the coast of Ireland or something like that,” Lennon once said, “looking at our scrapbook of madness.” But he’d probably still be keeping an eye on the world – by becoming an Apple Computer advisor, or a wise counsel to Elon Musk, or setting up a quiet but influential Lennon think-tank foundation. Or maybe he’d have preferred a nice game of chess.

20 Greatest Comeback Albums

How an Old Beatles Song Connected David Bowie With John Lennon