How the New ‘Halloween’ Fixes Something That’s Been Broken in the Franchise Since the Very First Sequel

The very first shot in David Gordon Green’s Halloween is a close-up of a clock. A later scene is set entirely around a Back to the Future pinball machine. Dates are constantly referenced; 40 years since serial killer Michael Myers last escaped from captivity; 15 years before that he murdered his sister. Time is clearly important to what Green is doing.

But it’s more specific than that. The film’s opening credits, a riff on the famous opening of John Carpenter’s Halloween and its slow zoom in on a jack-o’-lantern’s eye, features a rotted pumpkin slowly returning to life. In addition to being a cute nod to Carpenter’s film, the reverse time-lapse photography and the image of a decayed husk being restored to its former glory tips Green’s hand — because his Halloween is about to go back to the very beginning of the franchise and erase each of the nine previous sequels in order to undo the key decision that has hamstrung the Halloween series for almost 40 years.

Technically, Green’s sequel erases every decision in the Halloween franchise since the first one. It ignores all seven previous Halloween sequels (along with the two Rob Zombie reboot films, obviously) and imagines an alternate timeline where only the events of Carpenter’s Halloween took place. Paul Rudd versus a Druid cult? Sorry, never happened. Michael Myers saved from certain death at the bottom of a mine shaft by a weird old hermit? Doesn’t ring a bell (even though suburban Illinois is famous for its thriving population of weird old hermits). Busta Rhymes staff-fighting Michael Myers? Nope, no chance.

All of these questionable twists — okay, maybe not Busta Rhymes fighting Michael Myers with a bo staff, but the others — can be traced back to one ill-fated line of dialogue that, little by little, pushed Halloween into this nightmarishly silly territory: The moment in Halloween II when Dr. Loomis discovers Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) is secretly Michael Myers’ sister.

There isn’t even a hint of a family connection between the two characters in the original Halloween. In that film, Laurie and her friends are targeted by Michael Myers purely by chance. Myers, who murdered his sister when he was six years old, escapes incarceration and returns home to Haddonfield, Illinois on the 15th anniversary of his crime. That same day, Laurie’s father, a local real-estate broker, asks Laurie to drop off a key to the Myers house on her way to school. When she does, Michael — who’s hiding in the house — sees her, fixates on her, and then begins following her all over town.

While John Carpenter did co-write Halloween II with his creative partner from the first film, Debra Hill, he’s not shy about admitting he took the job primarily for the money and didn’t deliver a particularly great script. His primary inspiration for the Halloween II screenplay was, in his words, “Budweiser.” Every night, he’d sit down at his typewriter with a six pack and bang out pages. “What in the hell can I put down?” he would later remember thinking. “I had no idea. We’re remaking the same film, only not as good.”

Eventually, Carpenter went even further, calling Halloween II an “abomination.” And he was similarly displeased with the Laurie/Michael sibling twist — a twist he himself created (albeit under alcohol-fueled, financially-motivated duress). Carpenter remains adamant he and Hill had not planned Laurie and Michael’s mutual parentage all along; it was a pure and simple retcon, designed, Carpenter says, because he had been hired to write a movie where he “didn’t think there was really much of a story left” to tell.

He had a point. Because the first Halloween ended on a cliffhanger — psychiatrist Sam Loomis (Donald Pleasence) shoots Michael and sends him falling out a second-story window, and then his body mysteriously vanishes just seconds later — the decision was made to start the sequel immediately after the first film. Then the question becomes how do you keep Laurie — the sole survivor of the first Halloween — around? If Michael Myers is just a lunatic with a mask and a knife, what possible motivation could he have to chase after this woman a second time? Eventually, Carpenter (in association with Anheuser-Busch) found a solution: Laurie wasn’t a random girl, she was the girl — Michael’s other sister. To him, she was the girl who got away.

As retroactive explanations go, it’s not terrible. For whatever reason, Michael fixates on his sisters. He killed the first in the prologue to the original film. 15 years later, he returns to finish the job. By the time Michael Myers returned in the aptly titled Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers, Jamie Lee Curtis had fled the franchise, so he instead transferred his fixation to his niece, Jamie Lloyd (Danielle Harris).

But while it makes sense that a maniac would obsessively pursue his female relatives, it also makes Michael Myers an infinitely less scary villain. In Carpenter’s Halloween, Michael is essentially the Boogeyman, the living embodiment of childhood fear. The closing credits refer to him as “The Shape.” He exists beyond mortal questions like why and how. He is a pure, malevolent Force. In Halloween II, and in pretty much every movie after that, he’s just a dude with a Freudian hangup on his sister and niece.

The original Michael is terrifying. He could come after you at any time, for any reason. The “explained” Michael is not. I’m not related to the Strodes, so why should I be scared? If you’re really worried about Michael Myers just stay out of Jamie Lee Curtis’ immediate vicinity and you’ll be totally fine.

Ironically, John Carpenter understood that giving Michael a motivation ruined him, despite the fact that he’s the guy who gave him that motivation. In 2014, he said the reason Michael worked in his film — and wasn’t nearly as effective in any of the sequels — was because he was conceived as “an absence of character.” In Carpenter’s eyes, the sequels, which later added Druids and runes as possible explanations of Michael’s immortality and superhuman strength, missed “the whole point of the first movie. He’s part person, part supernatural force. The sequels rooted around in motivation. I thought that was a mistake.”

It’s a mistake David Gordon Green’s Halloween finally corrects. It dismisses the Laurie/Michael connection in a line of dialogue (which is featured in the movie’s first trailer) about how the mythical sibling relationship between the two characters was just “something people made up.” Michael breaks out of incarceration not to finish what he started, but because this is the first opportunity he’s had in 40 years. (He’s being transferred to another prison, which works out about as well as it does in any movie where a prisoner is getting transferred — very, very badly.)

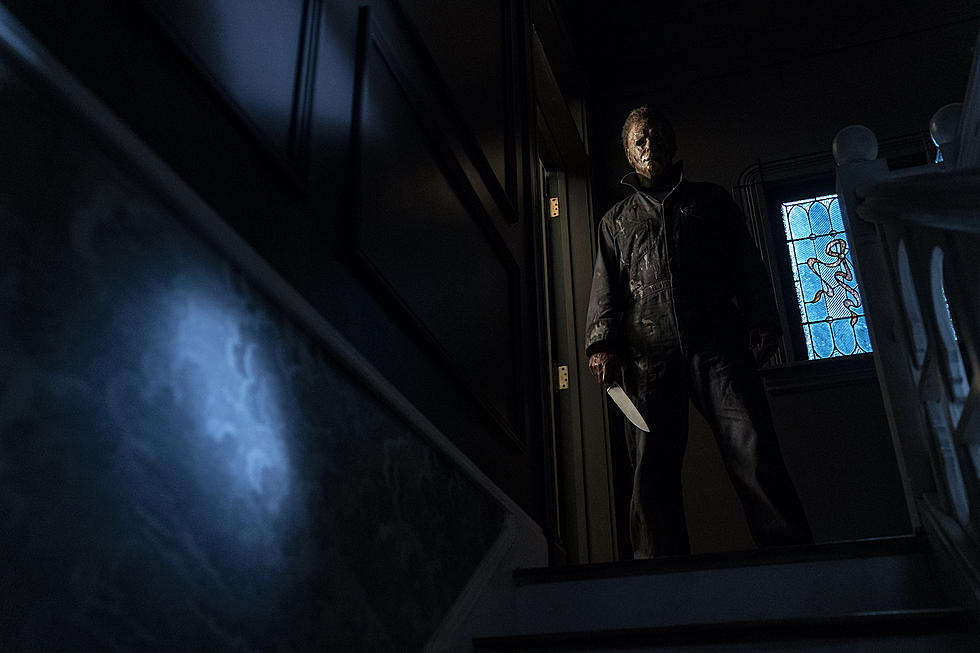

The most effective horror sequences of Green’s film are the ones that follow Michael as he resumes his violent activities on Halloween 2018 with zero rhyme or reason, following his repulsive instincts wherever they lead — from a hammer in a garage, to a house, to a butcher knife, to another house, and a new potential victim. He’s not killing because some mystical symbol demands it, or because a cult wants to harness his abilities to bring about the apocalypse. He does it because he’s a sick old man with a surprisingly high pain tolerance who gets off on causing misery and death. That’s a figure to fear no matter who you are.

I haven’t always been a fan of what I call “selective sequels” — follow-ups that ignore previous films in a franchise — because they usually strike me as lazy and reductive. David Gordon Green’s Halloween is different. Removing the burden of all that ridiculous continuity affords Green the time to consider Laurie Strode as a character — and as a survivor of a horrible trauma. Green may wipe the slate of all those crummy Halloween sequels, but he doesn’t remove the stain Michael’s violence left on Laurie’s soul. Simplifying the story allows him to make her character more complex; to show how some things can be erased, while others cannot.

More From Awesome 98